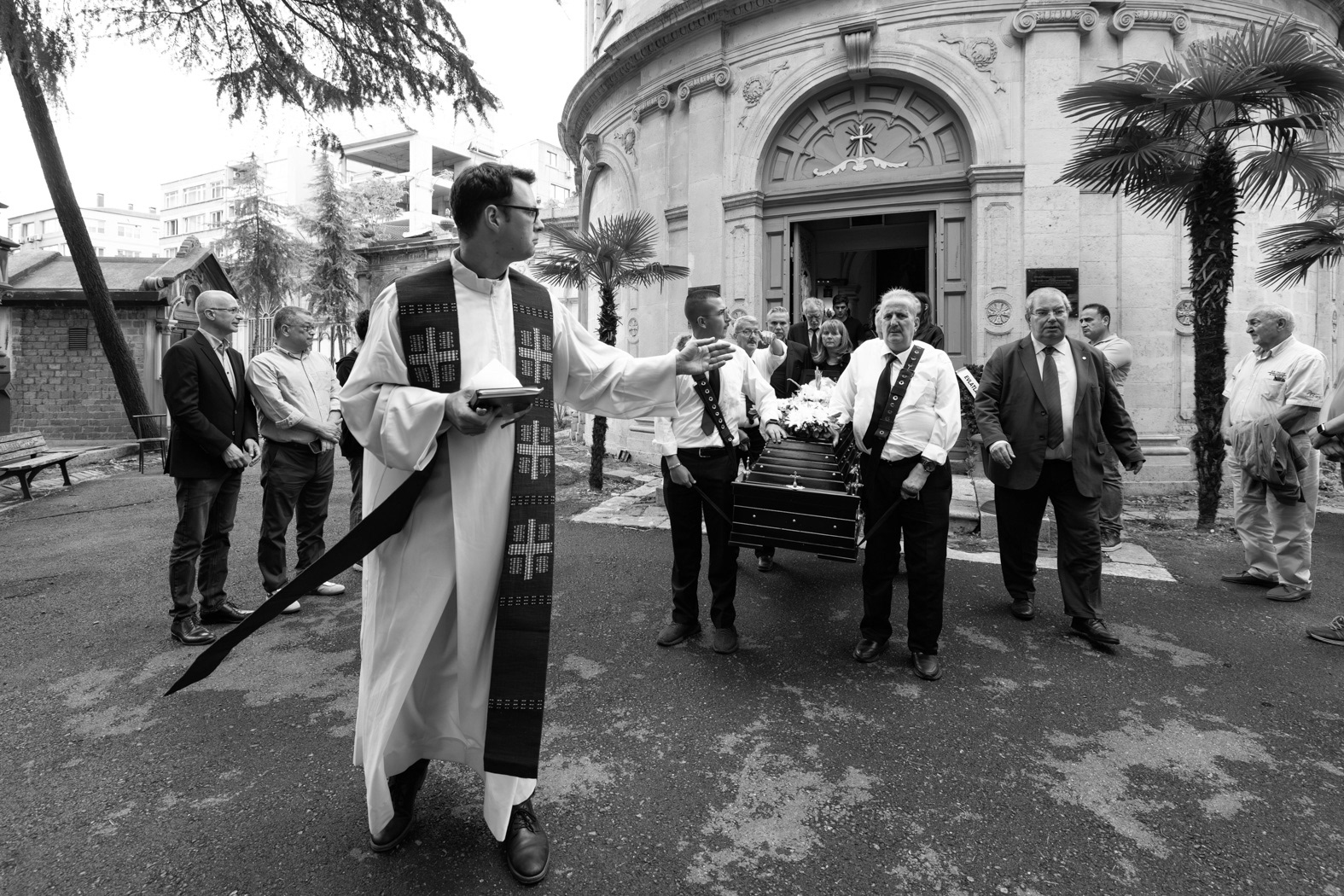

In general, minorities—and in particular Latin Catholics—were, for centuries, one of the essential pillars of these lands and of Istanbul’s multicultural fabric. They made profound contributions to the city’s identity in every sphere. The traces they left in commerce, art, architecture, and social life enriched Istanbul’s collective memory.

Yet for political, religious, and social reasons, they were torn away from these lands and forced to leave. This departure was not limited to people alone; it meant the loss of a way of life, a culture, a shared memory, and the will to live together.

They were our neighbors, our colleagues, our friends.

And today, it is not difficult to see what has filled that void, how a rich shared culture has been reshaped, and what the consequences have been.